· Philosophy · 14 min read

Bergson's Philosophy: A Dive into Fluidity and Critique

Exploring Henri Bergson's philosophy, its core ideas, and a critical analysis of its stance on irreducibility and reductionism.

The distinction between art on the one hand and science on the other is a tale as old as time. It is often depicted as the battle between the subjective and the objective, the qualitative and the quantitative. People like to put boxes around these concepts to explain away the inability of science to capture the essense of our experiences such as love, friendship, fear, and joy. But is this distinction really so clear-cut? Can we not find a middle ground where both art and science can coexist and complement each other? In this post, I want to explore the philosophy of Henri Bergson, a thinker who challenged the mechanistic view of the world and emphasized the fluidity and irreducibility of certain phenomena. I will also critically examine his stance in light of modern scientific perspectives.

A Notion of Irreducibility

Scientists aim to understand the natural world — or to put more plainly, we try to understand how stuff works. This often entails breaking the world down into smaller parts, analyzing them, and then reassembling them to understand the whole. For example, to understand how say the economy works, we might break it down into individual markets, analyze the behavior of consumers and producers, and then try to understand how these individual components interact to produce the overall economy.

By decomposing a problem in parts, we may sometimes notice that some information is not necessary to understand the problem. For example, if I throw a ball upwards, I must consider the gravitational pull from the earth, but not the gravitational pull Proxima Centauri (our nearest start other than the sun). One could include that gravitational pull of Proxima Centuari, but it would not change the accuracy of the prediction on when the ball land on the ground. This is the essence of reductionism: breaking down complex phenomena into simpler components to understand them better.

How does one decide which information to keep and which to discard? This is often a difficult problem and does not have a clear answer. In science we often apply Occam’s razor to create a model or understanding that uses the least number of things necessary to explain the observed. To unpack this further, this means that to understand the motion of a ball thrown upwards, we do not need to consider the gravitational pull of Proxima Centauri, but we do need to consider the gravitational pull of the Earth. This is because the latter has a much larger effect on the motion of the ball than the former.

Reductionism, therefore, should reduce the problem until we reach a minimal but sufficient set of components that can explain the observed phenomena. However, this does not mean that we can reduce everything to its smallest parts. Some phenomena are inherently complex and cannot be reduced to their individual components without losing their essence.

A phenomenon is called irreducible when it cannot be broken down into simpler components without losing its essential properties. That is, we need to understand irreducible observations we need to merely consider “fullness” of the observations. A concrete example would be that of consciousness. Some people argue that consciousness is an emergent property of the brain interacting with its environment. As such we cannot decouple the aggregate activity of the brain from the environment that its interacting with. This creates an intertwined feedback loop in which cause and effect becomes blurred and the whole cannot be understood by merely looking at its parts.

Now what does this have to do with Bergson?

Bergson’s Philosophy in a Nutshell

Bergson is one of the philosophers who has been most vocal about the limitations of reductionism and the need to consider the fluidity and irreducibility of certain phenomena. His philosophy is often seen as a reaction against the mechanistic view of the world that dominated the 19th century, particularly in the fields of physics and biology. Bergson’s work is characterized by two key concepts that are central to his philosophy:

- Durée: The subjective experience of time, which he contrasts with the objective, measurable time of clocks and calendars.

- Élan Vital: A creative life force that drives evolution and the development of organisms, which he sees as a dynamic, unpredictable process.

Let’s unpack these 2 concepts further to get a better understanding of Bergson’s philosophy.

The Concept of Durée or Lived Time

Consider our experience of time. Life progresses at a steady pace — days turn into weeks, weeks into months, and months into years. Our experience of time is not necessarily in terms of the seconds passed, but rather in terms of our memories and experiences throughout our life — it is lived and experienced. Similarly, we can think of our perception of time where sometimes time seems to fly by, while at other times it seems to drag on.

This concept of lived time is what Bergson refers to as durée. He argues that durée is fundamentally different from the objective, measurable time of clocks and calendars. While clocks measure time in discrete units, durée is a qualitative experience that cannot be reduced to mere numbers. In his view, durée is the essence of our lived experience, a fluid and dynamic process that cannot be fully captured by mechanistic or reductionist approaches.

The Force of Life: Élan Vital

In 1859 Darwin shook the world by publishing his seminal work On the Origin of Species. In it, he proposed a theory of evolution based on natural selection, which explained how species adapt and evolve over time through the survival of the fittest. This mechanistic view of evolution dominated biology for over a century, leading to a reductionist understanding of life as a series of adaptations to external conditions.

Bergson challenged this view by introducing the concept of élan vital, or “vital impulse.” He argued that life is not merely a series of mechanical adaptations but a dynamic, creative force that drives the evolution and development of living beings.

Bergson saw life as more than a series of adaptations to external conditions. He argued that élan vital represents the spontaneity and unpredictability inherent in living systems—a force that propels life toward novelty and complexity. For example, the emergence of entirely new forms of life, such as the transition from aquatic to terrestrial organisms, reflects a kind of creativity that, in Bergson’s view, cannot be reduced to mere chance or mechanical processes.

This vital impulse, according to Bergson, is not a physical force like gravity or electromagnetism but a metaphysical one—a continuous, dynamic push toward innovation and growth. It is what gives life its fluidity and capacity for transformation, distinguishing it from the static, predictable behavior of inanimate matter.

In this way, élan vital serves as a cornerstone of Bergson’s philosophy, emphasizing the irreducible and creative nature of life. Just as durée challenges us to rethink our understanding of time, élan vital invites us to see life as an unfolding process of endless creativity and possibility.

A Critical Examination

Bergon’s philosophy can be viewed as a critique of reductionism, which he sees as an inadequate approach to understanding the complexities of life and consciousness. By focusing on the irreducibility of certain phenomena, Bergson argues that reductionist approaches fail to capture the richness and fluidity of lived experience. He believes that science, while valuable, cannot fully account for the subjective aspects of human existence, such as consciousness and creativity.

At face value the notion of irreducibility seems compelling. It aligns with our subjective experience that indeed we don’t experience time as discrete units, but rather as a complex interplay of memories, emotions and perceptions. However, there are several concerns with Bergson’s philosophy that warrant a critical examination.

Conflating Subjective Experience with Mechanistic Explanation

Bergson often critiques reductionism for failing to capture subjective experiences like durée. A famous example is his argument for the perception of a melody — instead of hearing the individual notes, we experience the melody as a whole. He argues that this holistic experience cannot be reduced to the sum of its parts, as reductionism would suggest.

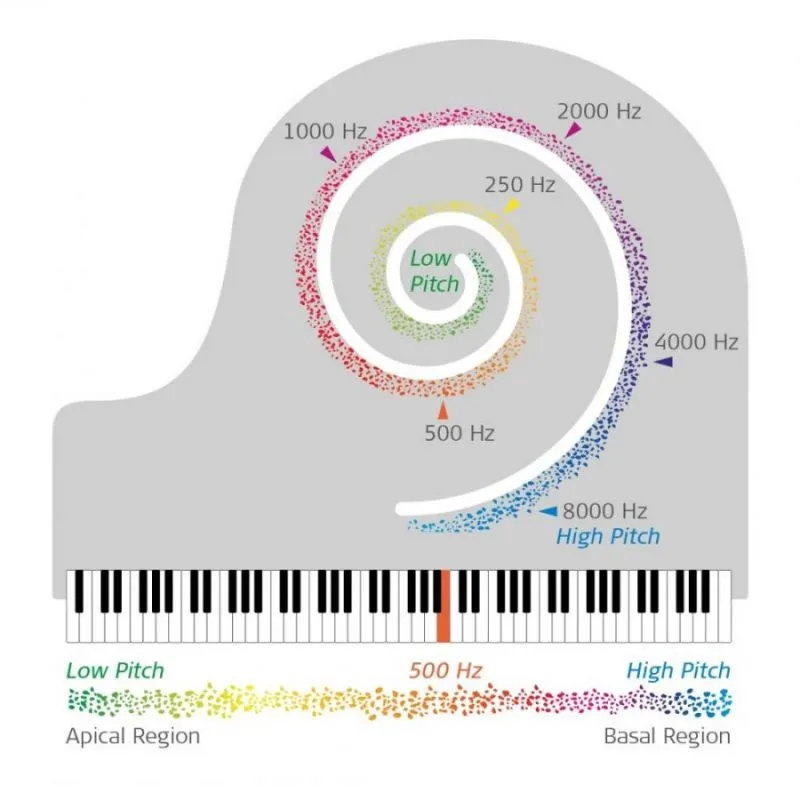

However, this critique conflates two distinct domains: the subjective, phenomenological experience and the causal driving mechanisms behind it. While it is true that our experience of a melody is holistic, this does not imply that the underlying mechanisms of sound perception are irreducible. Modern neuroscience has shown that our brains process auditory signals in a highly complex but ultimately mechanistic way, breaking down sounds into frequencies and patterns before reconstructing them into a coherent auditory experience. Similarly, visual perception involves decomposing a scene into edges, colors, and motion, which are then integrated into a coherent whole. These processes do not negate the richness of our subjective experience; rather, they provide a mechanistic understanding of how such experiences arise.

Sound is decomposed into frequencies by the cochlea, which then reconstructs the sound into a coherent auditory experience. This process is an example of how our brains break down complex stimuli into simpler components before reconstructing them into a holistic experience. Image credit

The perception, therefore could feel holistic, but this does not imply that the underlying mechanisms are irreducible. Instead, it suggests that our subjective experience is a product of complex interactions within our brain, which can be studied and understood through reductionist approaches.

By rejecting reductionism outright, Bergson’s framework is replacing it with something less precises and in the end less useful. While it is true that our subjective experience of time and consciousness is complex and multifaceted, this does not mean that reductionist approaches are inadequate or irrelevant. On the contrary, reductionism provides a powerful framework for understanding the underlying mechanisms that give rise to these experiences.

Imprecision in Key Concepts

One of the main challenges with Bergson’s philosophy lies in the imprecision of his key concepts, particularly élan vital. While evocative and thought-provoking, these ideas often lack the clarity and rigor needed for systematic evaluation or integration with scientific frameworks. For instance, élan vital is described as a creative life force driving evolution and the development of organisms, but it is presented as a metaphysical explanation rather than a scientifically testable hypothesis. Unlike physical forces such as gravity or electromagnetism, élan vital cannot be measured, observed, or empirically validated. This makes it difficult to assess its explanatory power or relevance in light of modern scientific understanding.

Modern evolutionary biology, for example, provides robust, evidence-based explanations for the diversity and complexity of life. Mechanisms such as genetic variation, natural selection, and genetic drift offer precise and testable accounts of how species evolve and adapt over time. These frameworks not only explain the emergence of novel traits but also allow for predictions about evolutionary processes. In contrast, élan vital remains speculative, offering no concrete mechanisms or predictive power. While Bergson’s idea captures the creativity and dynamism of life, it risks being redundant when emergent complexity and evolutionary theory already provide naturalistic explanations for these phenomena.

Similarly, Bergson’s concept of durée — the subjective experience of time—while compelling, is imprecise in its scope and application. Bergson contrasts durée with the measurable, objective time of clocks and calendars, emphasizing its qualitative and fluid nature. However, this distinction, while philosophically rich, does not engage with the ways in which subjective time perception can be studied scientifically. Modern neuroscience and psychology, for instance, have made significant strides in understanding how the brain processes time. Research shows that our perception of time is influenced by factors such as attention, memory, and emotional states, all of which can be studied and modeled. While durée captures the richness of lived experience, it does not provide a framework for understanding the underlying mechanisms that shape this experience.

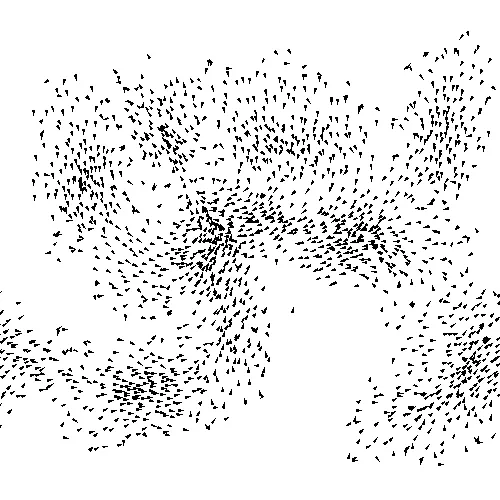

A murmurations an example of elan vital? How do individual birds form a complex pattern that seems to be more than the sum of its parts?

Bergson’s reliance on intuition as a method of understanding further complicates the precision of his ideas. Intuition, for Bergson, is a way of grasping the essence of fluid and dynamic phenomena that he believes cannot be fully captured by analytical or reductionist methods. While this approach is thought-provoking, it risks privileging subjective impressions over rigorous investigation. Intuition can serve as a valuable starting point for inquiry, but it must ultimately be tested and refined through empirical methods. Without this, Bergson’s concepts remain abstract and difficult to integrate with the scientific understanding of the world.

In the end, the imprecision of Bergson’s key concepts limits their applicability and relevance in contemporary discussions. While his ideas offer valuable insights into the richness of subjective experience and the limitations of mechanistic thinking, they often fall short of providing the clarity and rigor needed to engage with modern scientific perspectives. By grounding these ideas in more precise and testable frameworks, Bergson’s philosophy could achieve greater relevance and impact in bridging the gap between subjective experience and objective understanding.

Reconciling Bergson with Modern Perspectives

I am a complexity scientist, and to me concepts such as irreducibility and emergence often come out in discussions about the kinds of patterns we observe in real life. The field of complexity science is not void of any criticism (as I wrote about in the past). However, in my view we can reconcile Bergon’s idea by casting it in a more precise framework that aligns with modern scientific perspectives.

Take for example a flock of starlings. At dusk, these birds will fly in complex patterns, evoking the notion of a singular organism undulating into different shapes. It creates the subjective experience that these birds have formed something beyond themselves. Their behaviors have become smooth emergent interactions. Scientists, however, have been able to deduce that each bird in the flock actually follows 3 essential rules. If one combines these rules, the complex murmurations emerge. This is a prime example of how complex behaviors can emerge from simple rules, and how reductionism can help us understand these emergent phenomena.

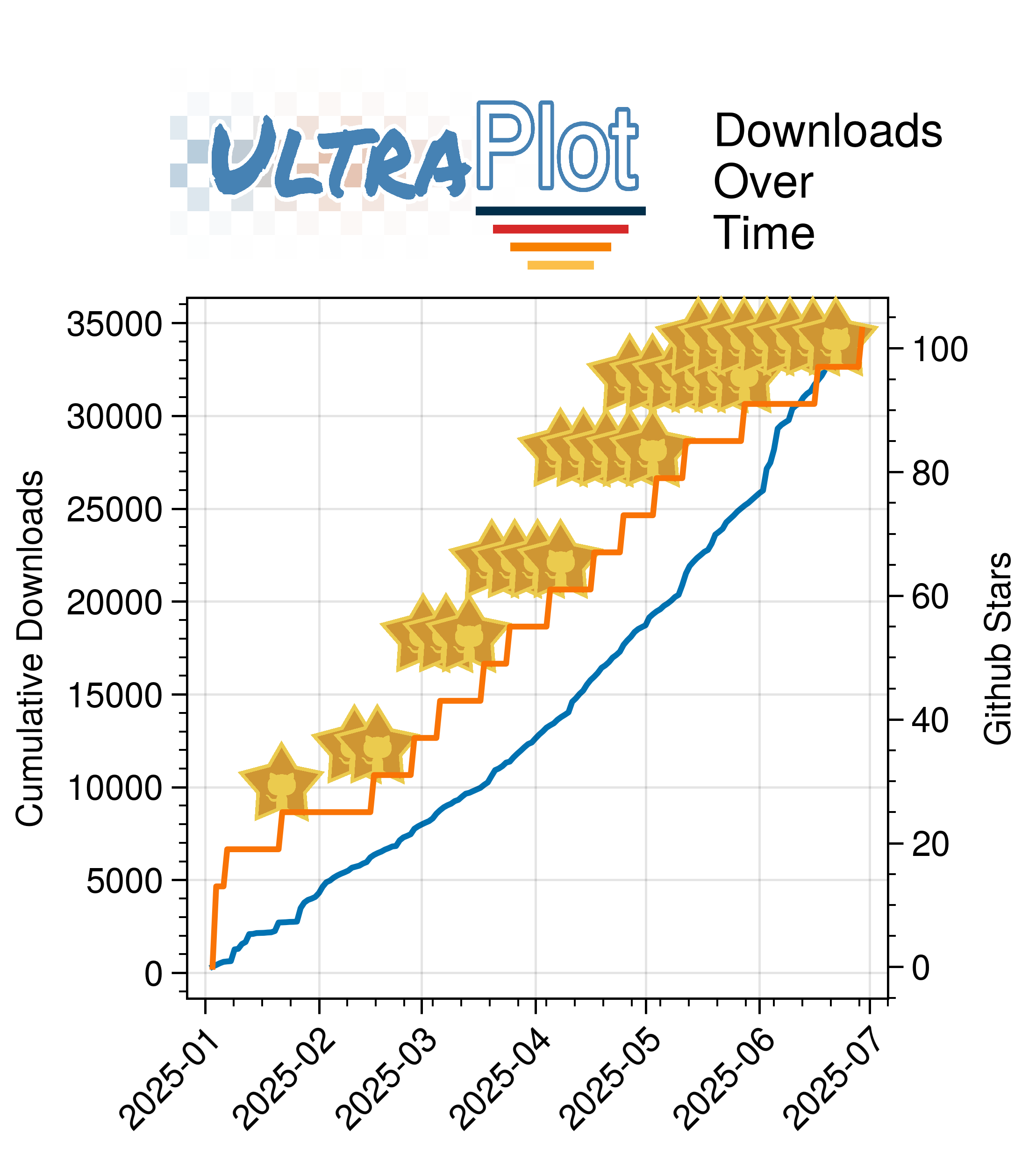

The Boids model can emulate complex murmurations by simulating the interaction of individual birds. Each birds follows simple rules that aim to be close to other birds, avoid collisions and match the velocity and directions of other birds. These simple rules produce complex subjective patterns, but can be understood through reduction. Here the simulation is performed in 2D.

Subjective experience is the output of the interactions with our body and the environment. This interaction creates a complex web of interactions that in its entirety produce our subjective experience. This is not to say that our subjective experience is not reducible to the parts, bu rather, we must emphasize that our interactions and the constituent parts create and consists of our experience.

In my opinion reductionism exists on a spectrum, where on the one hand we can have complete redundant information in a system whereby the parts are for example independent of each other. In this case we could isolate the system and just study the parts. As the correlations between the parts grow, we can create behaviors that are emergent (and therefore interesting). For a system to be completely irreducible there would be not way in which we can deduce the behavior of the whole to the parts — no such system exists in real-life. Consciousness is often depicted as one such system, but as the progress in neuroscience has shown us, we can indeed understand how parts contribute to the whole and as such the system is not irreducible.

Concluding Remarks

Henri Bergson’s philosophy challenges us to think deeply about the nature of time, consciousness, and life. While his critiques of reductionism highlight important limitations, they often rely on imprecise concepts that could benefit from greater clarity and integration with scientific perspectives. By reconciling Bergson’s insights with modern approaches, we can appreciate the richness of his ideas while grounding them in a more rigorous framework.

What are your thoughts on Bergson’s philosophy? Do you find his critiques of reductionism compelling, or do you think they miss the mark? Let’s discuss in the comments below!