· Casper van Elteren · Policy & Governance · 18 min read

Penguins, Poles and Politics

Utopia or hell? The geopolitics of the Antarctica Treaty System

Introduction

The polar ice caps evoke a profound duality of emotions. On one side, they present a pristine, austere beauty where penguins waddle in their natural “tuxedos,” nature’s own formal wear. On the other, they serve as a stark reminder of climate change’s devastating impact, as these magnificent ice formations gradually diminish, stirring feelings of environmental anxiety and urgency.

What often escapes public awareness is Antarctica’s surprisingly rich human presence. Beyond the expected community of scientists, the continent hosts military personnel, adventure tourists, and even a small contingent of semi-permanent residents. This human dimension raises fascinating questions about governance and sovereignty in one of Earth’s most extreme environments. Who has the right to live there? What determines research privileges? How is governance structured in this unique international space?

At the invitation of Dr. Maria Kleshnina and Dr. Ilva Sporne from the University of Queensland, I traveled to Antarctica with Dr. Vítor V. Vasconcelos to examine governance challenges in this unique region. Our field observations informed a broader collaborative effort involving an international team of researchers, including experts from Monash University (Prof. Steven Chown), Queensland University of Technology (Dr. Zachary Carter, Prof. Michael Bode, Dr. Kate Helmstedt), the Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse (Dr. Marion Hoffman), and other distinguished institutions.

This multidisciplinary collaboration brought together expertise in environmental science, computational modeling, decision theory, and policy analysis to examine the complex dynamics of Antarctic governance. The Antarctic Treaty System stands as a remarkable achievement in international diplomacy, establishing an unprecedented framework for multinational cooperation and scientific research.

Operating on a consensus basis among its signatories, the treaty has successfully maintained Antarctica as a continent dedicated to peace and science for over 60 years. However, beneath this idealistic surface lies a complex web of competing national interests and contemporary challenges. The treaty’s implementation frequently reveals tensions between scientific, environmental, and economic priorities.

There is a striking juxtaposition in how modern global politics unfolds against Antarctica’s pristine landscape of penguin colonies and vast ice sheets. This contrast powerfully illustrates how human governance systems now extend to Earth’s most remote frontiers, raising important questions about our collective responsibility for managing and preserving this unique environment for future generations.

Our team’s diverse perspectives and methodological approaches have enabled a comprehensive analysis of these challenges, contributing to our understanding of how to better govern this critical region in an era of rapid global change.

What follows here is some of my notes taken prior to the meetingt on understanding how the ATS works and how it can be analyzed from a computational perspective.

Populating Antarctica: A brief history

Antarctica derives its name from the Greeks who believed that that Antarctica or Ανταρκτική was a lower continent that would “balance” the northern hemisphere. They reasoned that this hypothetical continent would be on the “opposite” of Arktos — the bear shaped constelations of Ursa Minor and Ursa Major.

Stories from New Zealand tell of a time where Polynesians discovered Antarctica welll before the seafairing Westeners did, however some research contests these facts. Nathaliel Palmer was the first Westener to sight Antarctica in 1820. He was an American sealer who was looking for new hunting grounds. He was followed by the British explorer James Cook who circumnavigated the continent in 1773. The first landing on Antarctica was made by the British explorer John Davis in 1821. In its early days, the interest in antarctica was due to its potential for whaling and sealing — both priced commodities in the 19th century. Luckily, these practices have been banned in the 20th century.

Antarctica is denoted as the region south of the 60 degree latitude line. Its landmass is about 40 percent larger than that of Europe with the majority of the mass being below the South Pole, and is surrounded by the South Sea.

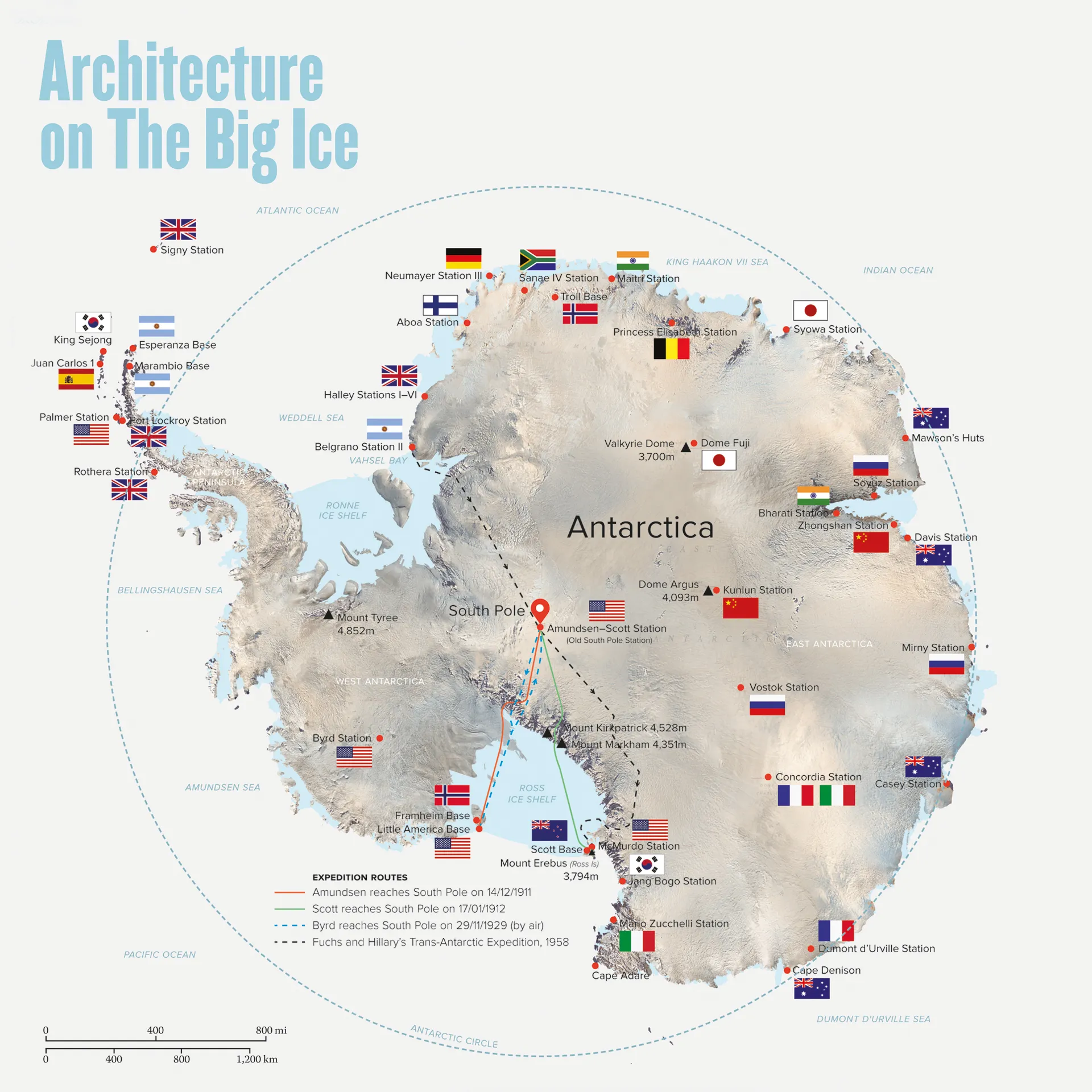

The population of Antarctica is primarily researchers, and supporting staff. It has no commercial industries, no towns, no permanent residents. There are about 60 scientific bases in Antarctica of which 36 are occupied all year round. Each base having around 50-60 people in summer and 10-20 people in winter timer. Antarctica, in short, is a desolate place — that you can visit as a tourist, but not live in.

The Establishment of a Scientific utopia

The reason why currently there are mainly scientists living there, is not because of its desolate nature or not wanting to become an extra in the next happy feet movie. Antarctica, in fact, has a rich history that is filled with international influence.

Initially, separate countries laid claim on the continent. Seven sovereign states — Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom — have made eight territorial claims in Antarctical. These claims were all made in the 20th century, and are not recognized by the rest of the world. The reasons for making these claims varied from resource potential, strategic value, military value (especially during the cold war), historical explanations to scientific value.

Most of the countries lay claim to specific sectors of the contintent that are largely separate from one another. The exception being the United Kingdom. Argentina and Chile claim parts of the territory claimed by the United Kingdom. These claims are largely based on historical precedent and the rule (and consequent war) of the Falkland Islands.

As the Second World War came to an end, and the cold war was in full effect, Antarctica became of interest by the two ruling super powers that were increasingly pointing nuclear weapons at eachother. These claims were put to a halt with the signing of the Antartic Treaty System (ATS) in 1959 which halted all further claims of terrority in Antarctica. It established Antarctica as a scientific preserve, and banned all military activity, nuclear tests and nuclear dumping, and mining activity on the continent.

The treaty is particularly interesting, as it is internationally heralded as the gold standard for stewardship of a region and wildlife preservation. It promotess international collaboration and scientific research. At the sametime, the region is not void of international influence and politics and shows a potential for scientific research on the decision making process.

How to Contribute in Antarctica?

The treaty was signed by the original claimants of the country but also Australia, Belgium, France, Japan, New Zealand, Norway and South Africa expanding the total countries to 12 that recognized the territory. The treaty came into effect in 1961. Since then, the treaty has been signed by 54 countries, and has been ratified by 29 countries.

In principle, any country can contribute to the scientific aims in the area. Membership is not required as long as the treaty is respected. Membership to the Antarctic Treaty exists in two flavors.

First, consultative parties, which are countries that have been active in the region and have been involved in the decision making process. These members can participate in the decision-making process andh ave voting rights. They are the prime workforce behind the scientific research activity in the area. There are currently 29 countries in this group.

The second group consists of non-consultative parties, which are countries that have shown interest in the region but are not involved in the decision making process. They can attend meetings but cannot vote on any issus. This group currently consists of 25 countries.

Key requirements for working in the region is that activities must be peaceful and adhere to the rules outlined in the treaty. The treaty also requires that all scientific data be shared with the rest of the world, all acts must protect the environment by complying with environmental protection protocols, and coordination with other countries must be performed.

The Taxonomy of the Decision Making Process in Antarctica

The decision making process within the ATS is often heralded as the gold standard for wildlife preservation. It is therefore warranted to closely examine how the ATS is structured and what the decision making process looks like. As a preamble, the Antartic Treaty System is rooted on the original Antarctic Treaty (1959) and the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (1991). The joint outlines the core principles and rules. It should be noted, however, that these rules are not enforceable directly only through international law. For each person present in Antarctica, the laws of their home country apply.

The ATS consists of different organs that are responsible for different aspects of the decision making process or provide support for the decision making process. In total 5 major organs can be identified: ATCM, CEP, SCAR, CCAMLR, and the CCAMLR. Broadly speaking, ATCM makes decisions, CEP provides environmental policy and protection, CONMAP provides practical operation and logistics, while CCAMLR focuses specifically on ecosystem managing in marine life and fisheries.

The primary decision organ in the Antarctic Treaty System is the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM). The ATCM is the highest decision-making body of the Antarctic Treaty System — all other committees or programs report directly to the ACTM and it is the organ that sets policy directions. It meets annually and is attended by all Consultative Parties and Non-Consultative Parties. The ATCM is responsible for the implementation of the provisions of the Antarctic Treaty and the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. The ATCM is also responsible for making recommendations to the Parties on all matters concerning the implementation of the Treaty and the Protocol.

The Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP) is an official body to the ATS and provides scientific input on things such which areas to protect by appointing Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs), Antarctic Specially Managed Areas (ASMAs), and other environmental protection measures. It performs environmental monitoring, waste management and emergence response, and tourist management. The CEP also provides advice to the ATCM on environmental matters.

The Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) is an international body (read non-governmental body) that provides idependent scientific advice to the ATCM. It is responsible for the coordination of scientific research in the region and provides advice on the implementation of the ATS. It is also responsible for the coordination of scientific research in the region and provides advice on the implementation of the ATS.

The Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs (COMNAP) supports the ATCM by mainly focusing on logistic matters and coordinatiion between the different bodies of the ATS. They often work together with SCAR to provide logistical support for scientific research.

The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) is responsible for the management of marine life and fisheries in the Southern Ocean. While it does have the power to make legally binding conservation measures for its members, it’s not the only ATS body that can make binding decisions (the Antarctic Treaty and Madrid Protocol also contain binding obligations).

Important to note is that the composition of these bodies are not the same across each body. For example, the ATCM consists of 54 total parties of which 29 have voting rights. Membership of the CEP is limited to those parties that have ratified the protocol. There are some countries that are a part of the ATCM that have not ratified the protocol, e.g. Switzerland, Colobmia, North Korea, and Papua New Guinea. Similarly, members of CCALMR cna include nations that are not part of the ATCM, e.g. China, Russia, and the EU (as a whole). Lastly, CONMAP consists of 30 members that must be from the Treaty Consultative Parties — which are those countries that have voting rights and decision power within the ATS. To become a member of CONMAP, a country must have a national Antarctic program and have been active in the region for at least 3 years or be part of the original signatories of the treaty.

The ATS in sum is complex of different organs that aim to promote peaceful collabrations through science. Yet, recent documents indicate that not all parties involved in Antarctica share its peaceful endeavor. In particular, some parties have been accused of using the region to explore for natural resources in particular for uranium. With the use of so-called dual use technologies actors can hide their intentions by means of scientific proposals. Furthermore, recent documents from the EU indicate that Russia, and China in particular are becoming increasingly disruptive in the region. The EU has called for a more active role in the region to counter these threats.

Playing for Poles: A Game Theory Analysis of Antarctic Governance

From a computational perspective, the politics in Antartica forms a rich base that is on the one hand “pure” in the sense that it does not concern immediate intercountry rivalry or disputes: the area is designated for scientific discovery. On the other hand it is not set in a vacuum but rather experiences effects from exactly these rivalries albeit not directly. This puts the ATS in a unique position where it can be analyzed from a game theoretical perspective.

Before I identify potential sources of conflict, it is important to denote the difference between an individual entity in the context of collective action. In particular, I will try to answer the question: what does it consistute to make a decision? How does the individual relate to the whole and how can place this within the context of the ATS?

Defining the Individual, Decsision Making, and Collective Action

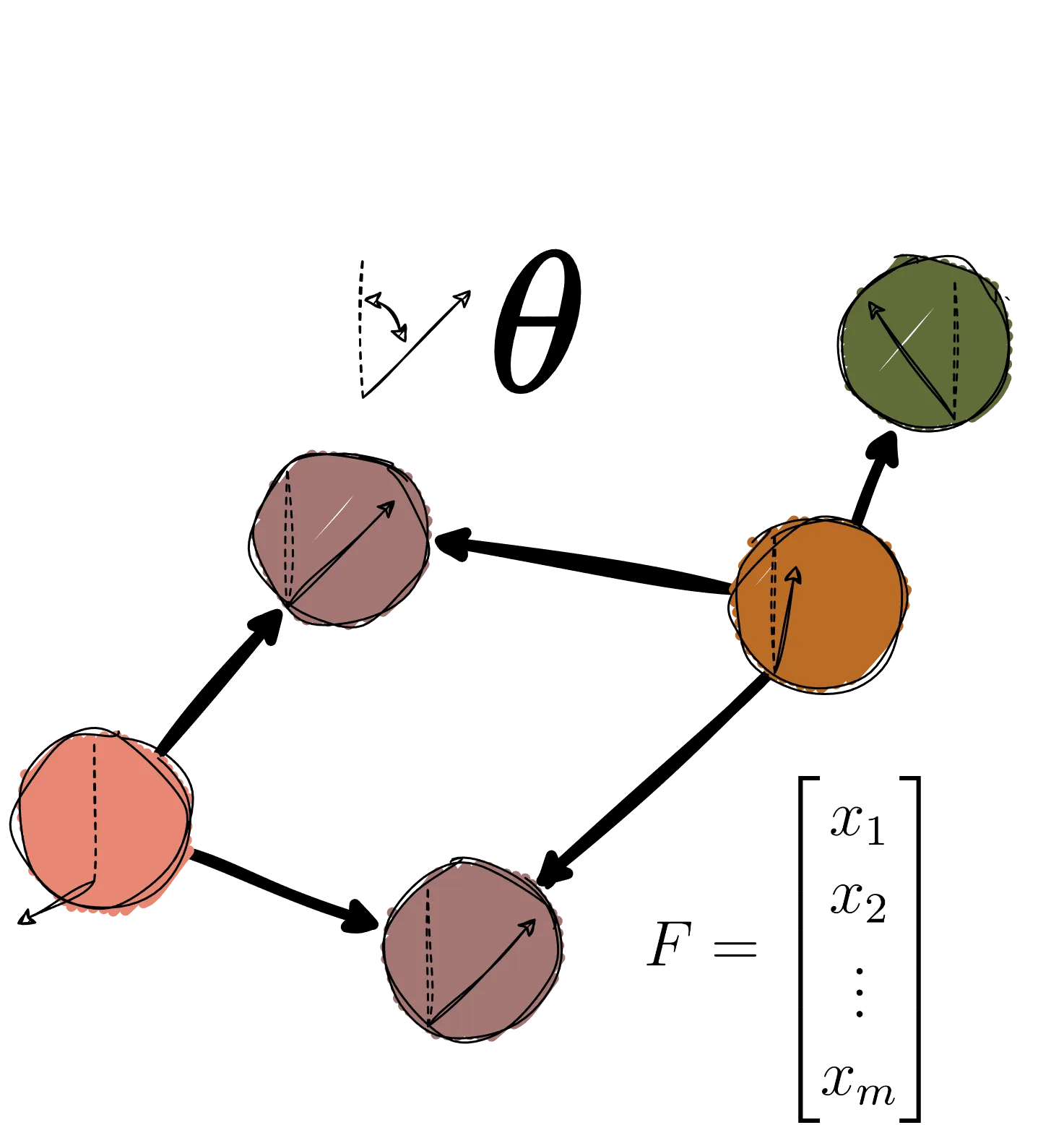

The individual serves as the fundamental unit of analysis in understanding collective action. Each person possesses unique preferences, beliefs, and capabilities that shape their decisions. These decisions emerge from a complex interplay of internal motivations and external constraints.

Decision-making operates as a process where individuals encounter choice points or “forks in the road.” These moments present options, each carrying different potential outcomes and requiring different resource investments. The decision-maker must evaluate these options within their contextual environment, considering both immediate and long-term consequences.

The evaluation process involves weighing multiple factors: First, there are the material resources available - time, money, physical capabilities, and other tangible assets. Second, there are social resources - relationships, reputation, and influence within relevant communities. Third, there are psychological resources - emotional capacity, willingness to take risks, and personal values.

One may argue that this is consequentialist approach to decision making, but I would argue that deontologic choice fall within this framework as well. Deontological stances, are nothing more than a high weight on a certain resource based on certain value or belief. This belief can be irrational or rational, but it is still a resource that is weighed in the decision making process.

Decisions rarely occur in isolation. The social environment heavily influences individual choices through established norms, cultural expectations, and institutional frameworks. These environmental factors can either constrain or enable certain choices, making some options more attractive or feasible than others.

The formation of collective action builds upon these individual decision-making processes. When multiple individuals recognize aligned interests and potential mutual benefits, they may choose to coordinate their actions. This coordination requires overcoming various challenges:

First, participants must establish trust and communication channels. Second, they must agree on common goals and acceptable methods. Third, they must develop mechanisms for sharing resources and distributing benefits. Fourth, they must maintain commitment despite potential setbacks or competing interests.

Successful collective action emerges when these challenges are effectively addressed through formal and informal arrangements. These arrangements might include explicit agreements, shared understanding of roles and responsibilities, and mechanisms for addressing conflicts and adjusting strategies as circumstances change.

The sustainability of collective action depends on maintaining alignment between individual interests and group goals. This alignment requires ongoing attention to changing circumstances and adaptation of strategies to ensure continued mutual benefit for participants.

To put this back into perspective, we can consider the ATS as a form of collective actions in which individuals (countries) pursue individual interests while weighin the cost and benefits of pursueing these interests. The ATS is a formal arrangement that establishes rules, norms, and procedures for coordinating activities in Antarctica. It provides a framework for addressing common challenges, sharing resources, and promoting scientific research while protecting the environment.

Taking a birds-eye view, we can see that the system can be conceptualized as network in which edges are weighted by trust. Agents aim to minimize their decoherence by aligning with potential partners. Given feature vector

Interesting Mechanisms to Leverage For Computational Modeling

Now that I have outlined the dynamics for the different entities, we need to specify this to the unique characteristics of the ATS.

Gateway States — Access to the Antartica

All countries are equal but some are more equal than others. Argentina and Chile, have a unique postiion in the ATS. First, they were one of the original 12 that signed the treaty in ‘59, making historically a strong claim moving forwards. Second, Argentina and Chila are uniquely position to more readily travel to and from Antarctica. This is due to their geographical location and the fact that they have the most developed infrastructure in the region. This gives them a unique advantage in the region. This advantage can be leveraged in the ATS to gain more influence in the region. This makes aliance formation with these countries in particular important — in fact this is the strategy that China and Russia are currently maintaining.

Sequence Effect of Chair

The chair in the ACTM is rotated by alphabetic order according to their english name. This unique sequencing can be leveraged to influence the voting based on where in the order the country is. A party may align in preparation of the party’s turn, making them more amenable to address points in the meeting that are of interest to the party. This can be leveraged to influence the voting outcome. Furthermore, working papers and information papers can be submitted prior to the meeting making them more likely to be accepted if the party or a fellow ally is in the chair.

Consensus versus Majority Voting

The type of voting will have major impact on the kind of dynamics to be expected. Since the original formulation of the treaty, only 12 parties were involved. Decisions were made through consensus voting which ensured that each member could not be outvoted. However, now that the number of parties has increased, consensus voting becomes more difficult as all parties must align to reach consensus. If no consensus is reached, a fallback mechanism is used where the proposal can be amended and accepted by 2/3 majority. This could potentially be leveraged to remove parties that are against the proposal and thus increase the likelihood of the proposal being accepted.

Changes in Political Climate

When Russia invaded Ukraine, it created shockwaves around the world that affected major economies. These waves even reached the shores of Antartica. In the wake of the invasion, the US and EU imposed sanctions on Russia. Since Russia was one of the original signatures of the ATS, it creates stresses among the alignment of goals for Russian presence in the region and other actors. According to a recent EU report, this shift caused increasing ties with China and a persistent effort for Russia to block proposals of new direction in the ATCM. The effects of external political events can have major impact on the dynamics of the ATS, in particular it would be interesting to see how changes in external conditions would change the alignment of parties in the ATS.

Outlook

Politics in Antartica offers a unique opportunity to study collective action in a controlled environment. The ATS provides a formal structure for coordinating activities in the region, promoting scientific research, and protecting the environment. However, the system faces challenges from increasing geopolitical tensions, resource exploitation, and environmental degradation. By applying game theory and computational modeling, we can analyze the dynamics of Antarctic governance, identify potential sources of conflict, and explore mechanisms for promoting cooperation. This research can inform policy decisions, enhance international collaboration, and contribute to sustainable management of the region.